I can understand the simple wish of rail passengers to have a train service that they can rely on. I can understand rail union’s wish to continually improve the pay and conditions of its members. I can understand the rail company’s wish to maximise its return on investment. I can understand the British government’s wish to ensure the railways are in a fit state to support a growing world city without annual subsidies – it has many demands on its purse. I can understand the BBC’s wish to be seen as being even handed in all political debates. What I can’t get a grip on is why we have not found a mechanism to resolve the conflicts inherent in these wishes.

It is easy to put the blame on one or more of the actors in this drama. There are those who would renationalise the railways to remove the capitalist gauging of the system. There are those who would blame the rail unions for over egging the safety case when it is all about money. Others would blame the government for the inadequate design of the rail franchise.

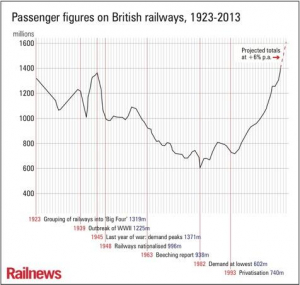

Southern Railways might be ineffectual – I don’t know; but I do remember being told by people who joined the railways in the nineties from other transport industries telling me how antiquated the management was from British Rail. New Virgin Rail staff told me how the “can do” attitude in Virgin Atlantic was difficult to inject into the “never done that here” attitude they found in the rail side. Whether this be so or not, the rail companies must be doing something right because rail travel’s eighty year decline ended at rail privatisation and rose rapidly afterwards. I know that correlation does not mean causation but try and explain that rise in passenger numbers any other way.

The rail unions have done especially well at their job. Train drivers have a well sought after pay package. Far higher than the free market would require. But they are ably assisted by the fact that they are in a monopoly industry and it is difficult for customers to go elsewhere for the same product. They would probably not fare so well in a competitive environment because their companies would go bust.

The BBC, as broadcasters go, does very well in its aim to inform, educate and entertain. But when it comes to binary debates it tries too hard to be even-handed. We saw it with the climate change debate, the recent referendum, as well as in the rail dispute. Give each side half of the time and the job is done. No it isn’t. Where are the questions that put each side’s assertions to the test?

I listened to a more extensive debate recently, which at least moved away from the drama and personality – peppered with a few vox pops of passengers’ poor experiences. It discussed what has been put over as the central theme of the conflict – safety.

The train operators said that we already have the safest railways in Europe. Is that true? No it isn’t. But the BBC did not challenge it. We are second safest after Luxembourg (killed or seriously injured people per passenger kilometer travelled). Near enough but still unchallenged. After Britain comes the Netherlands and our safety record is twice as good as theirs.

The rail unions say that their argument is based on safety. That a driver operating the doors is not safe enough – it needs a guard there to do it – even on a train designed and constructed for person operation. True, the BBC mentioned that surely there were government bodies whose role was to specifically ensure safety on railways but the rail union representative batted that one away by saying that those safety organisations were serving the British government’s hidden agenda. Not once did the BBC ask the rail union person the simple question “What is the comparative safety record between driverless trains, driver only operated trains and two person operated trains”. If the safety record is significantly different between these three levels of operating trains, then a case could be made. I would like to see the evidence in detail but driver operated trains are actually safer than the old types of trains – especially at the door-platform interface. The BBC has the resource to find out these facts before the interview and could challenge the rail unions on this matter.

Then came the rail union’s piece de la resistance. People feel safer if they are on a train with more than just the driver. I imagine that’s true (I do not know). Passenger perception is important and also there are a number of safety events on a train – that do not involve the train itself – that would be helped if a member of staff, other than the driver, was on board. Passenger illness for example.

Back to how to resolve this dispute and others like it. The two parties can talk. They can go to ACAS or other similar arbitration bodies. But it is very hard for these to work. The reasons are twofold: traditional negotiations are based on each side making the most extreme first offer and finding out who blinks first the second is that rail unions, in Britain, are far more powerful than the rail companies.

What I would suggest using, if all other routes to resolution are exhausted, is binding pendulum arbitration. In this case, each side – unions and management – give an independent arbitration body their best offer for a solution to the conflict. The arbitrator has to choose one settlement or the other in their entirety. The arbitrator may not cherry pick the “best” bits from each side. The great advantage of this method is that it induces each side to make their offer the most likely to be chosen by the arbitrator. The disadvantage is that the best solution might be different from those offered by either side. Whichever offer is chosen, the winner would be the travelling public.

0 Comments View now